You know that feeling you get when you are just in desperate need of a sieve for an unexpected day of sifting through creek sediments for 75 million year old shark teeth? No? Well, I didn’t either until last weekend when I found myself in this very situation. However, being in Mississippi for the weekend and having a few hours before a family wedding (congratulations, Matt and Cassandra!), my geologist fiancé Zebulon took me, his sister Hannah, and our dog Lucy on a last-minute trip in time to the Cretaceous in search of fossilized shark teeth hiding among the sediments of a small creek (and using some improvised kitchen tools for the search).

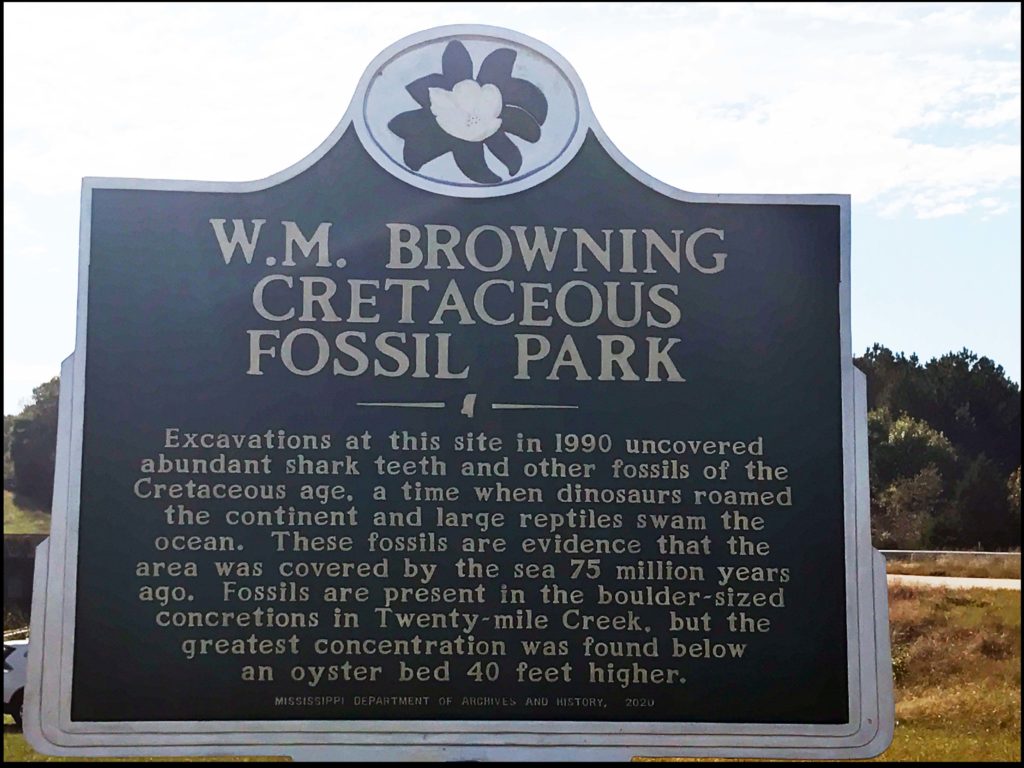

We headed out to Baldwyn, Mississippi, home to the W.M. Browning Cretaceous Fossil Park. Here, the discovery of numerous marine fossils in 1990 during construction on Highway 45 made national news as a great location to find shark teeth fossils, drawing people to come check out the site and try their luck at finding some teeth1. In fact, the news of the find was so exciting to the community that the local Booneville High School got funding through a National Science Foundation (NSF) grant to make the site a teaching field laboratory while the construction was taking place. This was the first type of grant that was awarded to a public high school1, truly demonstrating the power of linking the science research community with K-12 education (also a dream of ours here at Backyard Geology).

Setting the geologic scene

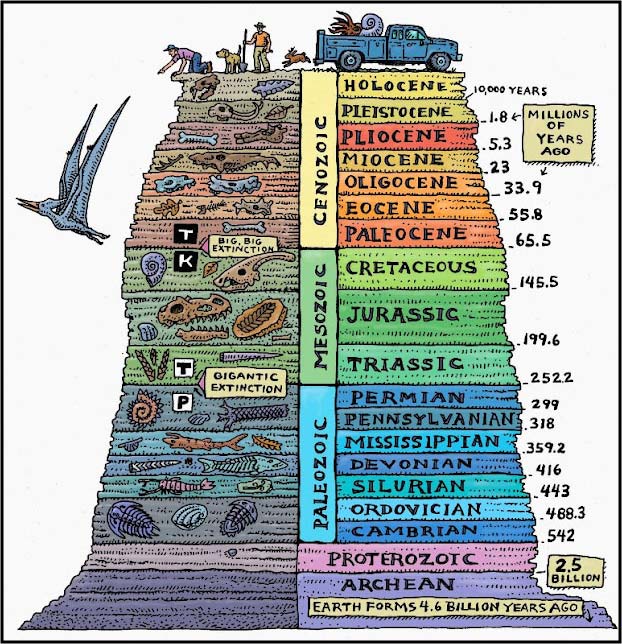

Most of you may know the Cretaceous period (145 to 66 million years ago) by what happened at the very end of it: the extinction of the dinosaurs. While this geologic period is certainly famous for its abundance of dinosaur fossils, paleontologists in North America also know this period as one with fascinating marine fossils due to the prevalence of the Western Interior Seaway. The Western Interior Seaway cut the North American continent in half during the mid-to-late Cretaceous (we talked about the Western Interior Seaway’s presence in New Mexico in our post on gypsum). In Mississippi, Cretaceous rocks and sediments exposed in the northeastern part of the state supply a variety of marine fossils. The W.M. Browning Cretaceous Fossil Park is no exception and fossilized evidence of invertebrate marine organisms like oysters, sponges, and bivalves (mollusks) can all be found here. But the really cool part is that we can also find fossilized evidence of marine vertebrates! These include crabs, lobsters, sharks, rays, bony fish, sea turtles, chimaeroids (fish with cartilage-based skeletons), and mosasaurs (an extinct marine reptile)1.

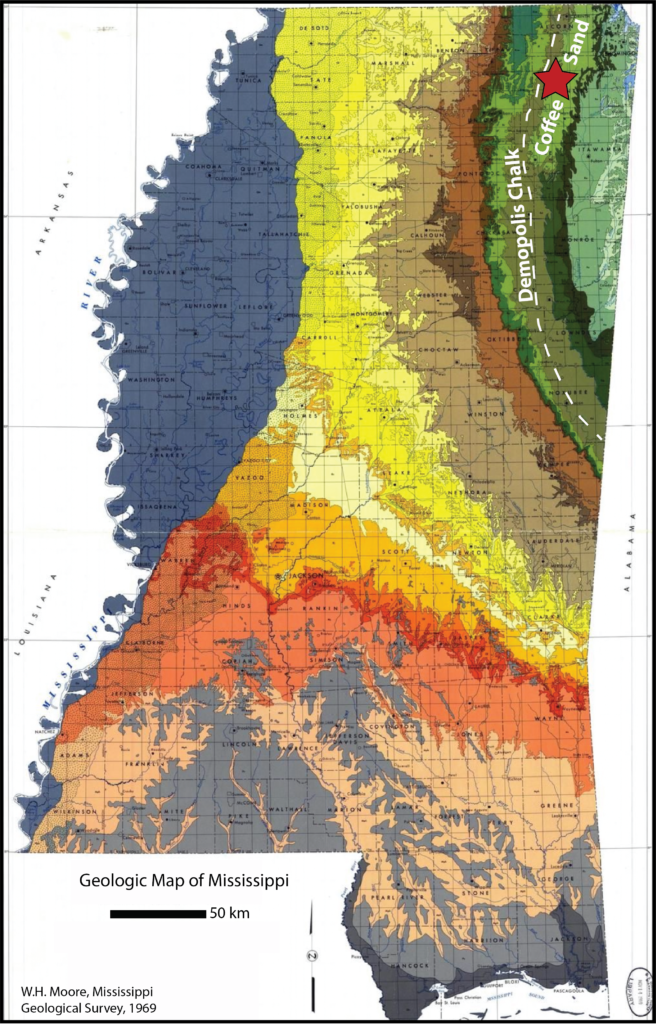

The shark teeth at the Browning Fossil Park site can be found mostly in the Demopolis Formation (a geologic formation is just a collection of deposits that formed under similar conditions and have similar physical characteristics). This formation is characterized by layers of calcite-rich clay, chalk, and sand. The shark teeth are found in sandy layers right where the Demopolis formation overlies (meaning lies on top of) the Coffee Sand formation. The Coffee Sand formation is characterized by river delta sediment layers interspersed with marine sediment layers (like the calcite rich chalks and clays more common in the Demopolis formation)1.

So what does all this mean? This tells us that our Cretaceous sharks lived in a warm, shallow sea where river deltas deposited sand to the marine environment. We also know that this environment was rich in the mineral calcite (we talked about calcite and its relation to marble in our post on acid rain). How exactly do we know that? Well, scattered throughout Twenty Mile Creek in the Browning Fossil Park are these strange, round boulders (strange because they are *very* round). These boulders are actually concretions1, meaning they are a mass of sediment that was glued in place by calcite precipitating through groundwater.

Sharks and shark teeth

One thing that is pretty unique about paleontology (the study of ancient organisms through fossils) is that it really bridges the gap between biology and geology. As a non-biologist myself, I learned a lot about sharks (that maybe some of you already knew). For example, sharks have a skeleton mostly made out of cartilage (similar to the stuff making up the harder part of your ear). This fact is actually very important in terms of where sharks are found in the fossil record.

Sharks have been around for quite a while throughout Earth’s history (or, at least, the part involving living multi-celled critters). The oldest shark-like fossil to date is from around 450 million years ago (during the Late Ordovician). The oldest shark teeth found so far are from 410 million years ago, leading to the question: wait? Were the earliest sharks toothless?? (It appears the answer is maybe, maybe not)3. Sharks had to wait until around 359 million years ago for their “Golden Age”. Yup! That’s what some folks call it!3, 4 During this time, sharks began to really evolve towards what we would recognize as a modern-day shark by the Early Jurassic Period (about 195 million years ago). Small, bottom dwelling sharks survived through the extinction of the dinosaurs and then got really, really big as they took advantage of the absence of other apex predators (the Megalodon shark lived during the Miocene Epoch and was up to 50 feet long and had a weight of up to 50 tons)5. Side note: if you want to find really cool Megalodon teeth – head to South Carolina! This past year, someone found a nearly one pound Megalodon tooth there!6

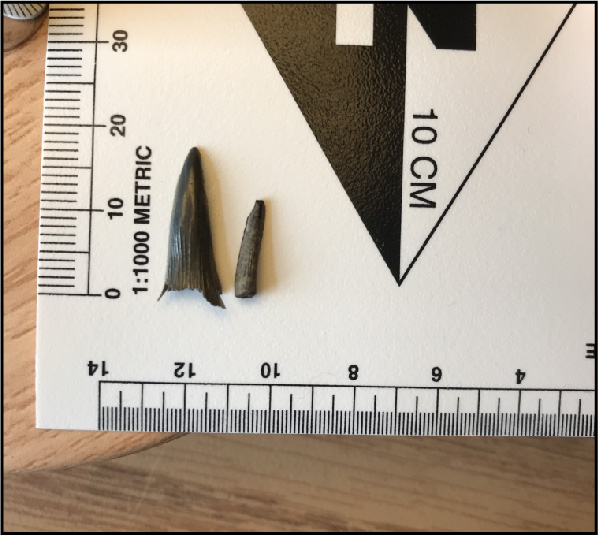

So why do we find so many shark teeth? Well, remember back to what shark skeletons are made of. Cartilage isn’t as easily preserved as bone in the fossil record over millions of years. So the shark skeleton fossils are rare. However, shark teeth are made out of dentin and enamel, which is harder than cartilage and can more easily survive in the fossil record4. We talked about how fossils are formed in our post on dinosaurs vs. chickens. But the important piece is that the softer organic material of the tooth must be protected from decomposition through quick burial and then replaced by a harder mineral. In the case of the teeth we found in the picture above, the mineral apatite has likely replaced the organic material, resulting in the black-colored teeth. Why are the teeth in the Browning Fossil Park so plentiful? Because shark can apparently make new teeth to replace old ones, meaning one shark can have up to 40,000 teeth in their lifetime!3 All those teeth per shark over millions and millions of years….yeah, that will add up. Shark teeth fossils are so abundant that Native American communities thousands of years ago even used shark teeth fossils for weapons, scraping tools, or even for religious ornaments7.

Goblin sharks

The majority of shark teeth found at the Browning Fossil Park are from goblin sharks (modern day latin name: Mitsukurina owstoni). Goblin sharks (perhaps the most aptly named shark for this day-of-Halloween post) are still around today. And they are pretty weird. A recent study described the feeding-style of a goblin shark off the coast of Japan. The shark juts out its jaw to grab at unsuspecting prey8. Sounds like a cool evolutionary trick (but looks pretty funny in reality).

References:

1 Manning, E.M. and Dockery, D.T., 1992. A guide to the Frankstown vertebrate fossil locality (Upper Cretaceous), Prentiss County, Mississippi (No. 4). Mississippi Department of Environmental Quality, Office of Geology.

2 Lockshin, S.N., Yacobucci, M.M., Gorsevski, P. and Gregory, A., 2017. Spatial characterization of cretaceous Western Interior Seaway paleoceanography using foraminifera, fuzzy sets and Dempster–Shafer theory. GeoResJ, 14, pp.98-120.

3 Davis, J. “Shark evolution: a 450 million year timeline”. Natural History Museum, London. https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/shark-evolution-a-450-million-year-timeline.html, accessed 30 October, 2021.

4 “Sharks”. Smithsonian. April, 2018. https://ocean.si.edu/ocean-life/sharks-rays/sharks, accessed 30 October, 2021.

5 Dykens, M. and Gillette, L. ”Megalodon Shark”. San Diego Natural History Museum. https://www.sdnhm.org/exhibitions/fossil-mysteries/fossil-field-guide-a-z/megalodon-shark/, accessed 30 October, 2021.

6 Leone, J. “Fossil hunter finds massive 6.45-inch megalodon tooth at South Carolina construction site”. Cox Media Group. https://www.kiro7.com/news/trending/fossil-hunter-finds-massive-645-inch-megalodon-tooth-south-carolina-construction-site/LK6BWKFK45EW7DPRZSYKRZ5BM4/, accessed 31 October, 2021.

7 Lowery, D., Godfrey, S.J. and Eshelman, R., 2011. Integrated geology, paleontology, and archaeology: Native American use of fossil shark teeth in the Chesapeake Bay Region. Archaeology of Eastern North America, 39, pp.93-108.

8 Nakaya, K., Tomita, T., Suda, K., Sato, K., Ogimoto, K., Chappell, A., Sato, T., Takano, K. and Yuki, Y., 2016. Slingshot feeding of the goblin shark Mitsukurina owstoni (Pisces: Lamniformes: Mitsukurinidae). Scientific reports, 6(1), pp.1-10.