It’s spring here in the Northern Hemisphere! The birds are chirping, the flowers are blooming, and the pollen is….everywhere. For allergy sufferers, pollen is an ever-present reminder that spring has sprung….and it’s here to make you just a little bit miserable. But, you’re in luck! We here at Backyard Geology have found the cure to your suffering: fossilized pollen!

When you think of the word fossil, what comes to mind? You may be thinking of something that looks like it could jump back to life and chase you through the fictional island of Isla Nublar. Or, perhaps, you are thinking of these cute little critters called trilobites, arthropods that scuttled around throughout much of the Paleozoic Era. But here, we are talking about tiny pollen fossils, comprising what we call “microfossils”. It may be really strange to think about, but pollen grains make pretty fantastic and useful fossils.

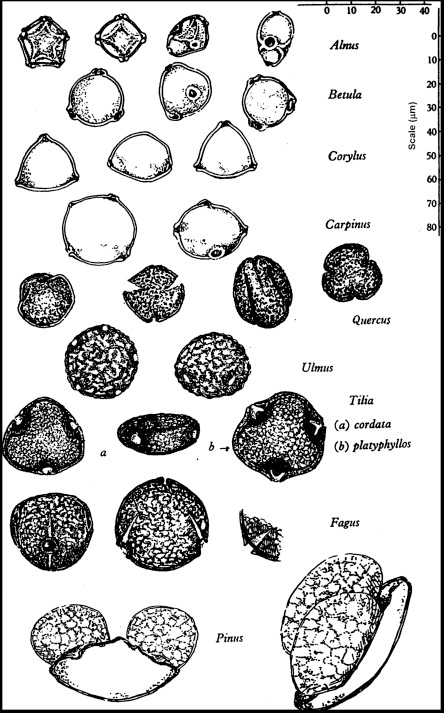

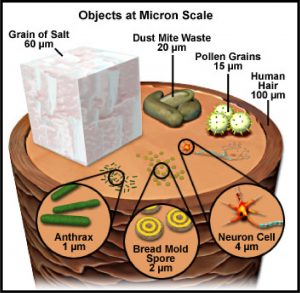

Pollen grains are small. Individual grains can vary from 10 – 150 µm (that’s “microns”)2. To give you some perspective, 1 µm is equal to 0.001 mm and the human eye can see objects only as small as 0.1 mm (so pollen is really, really small!). The yellow pollen “dust” you might see coating everything in sight during the spring is likely made up of many, many individual grains of pollen. For example, just 1 gram of honey can contain hundreds to millions of pollen grains3.

Pollen fossils: clues to an ancient climate

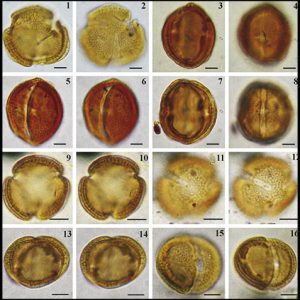

Pollen may be small but it is also mighty! Pollen has a strong outer layer called exine that is resistant to chemical changes that would cause lesser structures to crumble over time5. This strong outer wall makes pollen more likely to survive in the rock or sediment record over thousands to millions of years. Over time, the pressure needed to turn soft sediments into hard rock compresses the pollen grains, preserving the pollen grains together with the sediments into a sedimentary rock6. The study of pollen is called palynology and the study of fossilized pollen is paleopalynology (try saying that five times fast).

Pollen is the male gamete from plants that reproduce using seeds. The two major types of these plants are gymnosperms and angiosperms. Gymnosperms are cone-bearing plants whereas angiosperms are flowering plants. The fossil record tells us a lot about the evolution and diversification of plant life millions of years ago. While the earliest terrestrial (meaning land-inhabiting or not marine) plant life seems to have occurred around 500 million years ago, gymnosperms didn’t evolve until around 319 million years ago and angiosperms really blossomed (pun intended) around 150 million years ago8,9 (to give you some context: the dinosaurs went extinct around 65 million years ago….unless you really are visiting Isla Nublar that is). Pollen grains are actually one of the most abundant fossils of terrestrial plants3!

As long as we know which type of plant the pollen came from (and know what type of climate that plant liked to live in) we can get a clue as to the climate at the time and in the region where the pollen grains were originally deposited10. For example, 55 million year old pollen fossils from tropical plants found in rocks in Maryland tell us the climate at that time was wetter and warmer than it is now11. Sediment cores taken from oceans, seas, or lakes provide abundant pollen evidence for times that are a bit more recent. Pollen analyses have even been used to study the spread of olive cultivation across the Mediterranean around 3,000 – 5,000 years ago12.

So the next time you sneeze from pollen-riddled spring air, just picture the resilience and history these little grains signify. What makes you miserable today may very well ride through the rock record thousands or millions of years into the future!

References:

1Godwin, Harry. “The history of the British Flora.” The history of the British flora. (1956).

2Bradley, R. S. “Paleoclimatology: reconstructing climates of the quaternary”, 3rd edn. Academic.(2015).

3Palynology. University of Arizona: Geosciences, https://www.geo.arizona.edu/palynology, accessed 2 June, 2021.

4Mass Spectrometry 101. National High Magnetic Field Laboratory, 8 January, 2015. https://nationalmaglab.org/education/magnet-academy/learn-the-basics/stories/mass-spectrometry, accessed 3 June, 2021.

5Mach, J. “Open wide! Exine patterning and aperture formation in Arabidopsis pollen.” Plant Cell 24, (2012): 4311–4311

6Lab III: Plant Fossils and their Preservation: Conditions Required for Plant Fossil Preservation. University of California Berkeley, https://ucmp.berkeley.edu/IB181/VPL/Pres/Pres2.html, accessed 2 June, 2021.

7Barreda, Viviana, Luis Palazzesi, and María Cristina Tellería. “Fossil pollen grains of Asteraceae from the Miocene of Patagonia: Nassauviinae affinity.” Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology 151.1-2 (2008): 51-58.

8Pankau, R. Angiosperms vs. Gymnosperms. University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, 23 January, 2021. https://extension.illinois.edu/blogs/2021-01-23-angiosperms-vs-gymnosperms, accessed 2 June, 2021.

9Magallón, Susana, et al. “A metacalibrated time‐tree documents the early rise of flowering plant phylogenetic diversity.” New Phytologist 207.2 (2015): 437-453.

10Pollen: More Than Just an Allergen. UCAR: Center for Science Education, https://scied.ucar.edu/learning-zone/how-climate-works/pollen-more-just-allergen, accessed 2 June, 2021.

11Secrets of the Past Unlocked by Fossil Pollen. USGS, 13 June, 2019, https://www.usgs.gov/media/images/secrets-past-unlocked-fossil-pollen, accessed 2 June, 2021.

12Langgut, Dafna, et al. “The origin and spread of olive cultivation in the Mediterranean Basin: The fossil pollen evidence.” The Holocene 29.5 (2019): 902-922.

Interesting.mi’m fortunate I have never suffered from pollen, just have to deal with the mess outside in the spring when everything is yellow.

Yes! Me too, until I moved to the southwest and met Juniper pollen!! Thanks so much for reading!