This week we will talk about two-legged predators that first evolved during the Mesozoic era (248-65Ma). Their distant relative roamed the ancient world with a ruthless hunger for prey and at a terrifying size of 5 – 8 tons1, making it one of the main antagonists in this Hollywood blockbuster. Of course, what else could I be talking about besides the indomitable chicken and it’s evolutionary relationship to two-legged dinosaurs. And yes, that distant relative is the infamous Tyrannosaurus Rex or “T. Rex”.

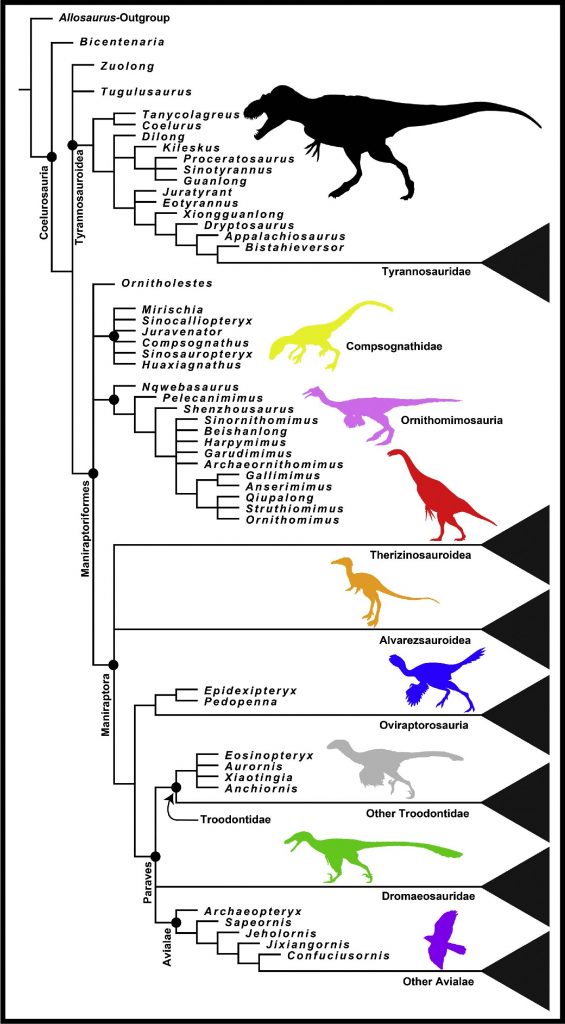

Chickens are part of the same phylogenetic tree as theropods, or two-legged dinosaurs2. A phylogenetic tree is a special tree that tracks evolutionary changes between related organisms. This means that, if a chicken were to do a 23andme test, they would find themselves linked to distant relatives including the T.Rex and velociraptor (I’m not sure if the chicken would want to reach out to those distant relatives, however). Now, in the phylogenetic tree below, you can see that modern birds are actually most closely related to smaller theropods (with weights between about 100 – 500 pounds)3. This is because an organism is most closely related to other organisms that are closer to it in the tree. So, we’ve come a long way in terms of evolutionary changes between a T. Rex and a chicken. However, the question is: when exactly did birds genetically split from dinosaurs?

From dinosaurs to birds

The evolutionary connection between dinosaurs and birds is actually somewhat of a contentious topic in the world of Paleontology (the study of ancient life through examination of fossils). It may seem like we know a lot about dinosaurs based on what you see in the movies but our knowledge of these ancient organisms is dependent on what we find in fossils. Fossils can form when an organism dies and happens to be buried quickly by silt or mud to protect the precious organic material from decomposing. Over time, the silt and mud turns into a sedimentary rock and the organic material is replaced by minerals, preserving the material as a fossil4. The chances of organic material being preserved as a fossil are very low. Just think of all the changes that can occur over millions of years! For example, if the sedimentary rock a fossil is in is metamorphosed (think back to our friendly metamorphic rocks from this post and this post), the fossil will be destroyed by the changes the rock endures! This means that paleontologists may be just one more fossil away from a discovery that changes our understanding of the ancient world. That’s exactly what happened with the latest discovery of the “wonderchicken”, giving us more information about the evolution from dinosaurs to birds. Read on to find out more!

Earliest direct ancestor to modern chickens

A recent scientific study published in 2020 discusses the discovery of what could possibly be the earliest known direct ancestor to a modern chicken5. Scientists discovered the nearly complete fossilized skull of what they are now calling “Asteriornis Maastrichtensis”, named after “Asteria” a Greek Goddess that turns into a quail (yes! If you discover a fossil you get to name it!)5,6 Before this fossil, one of the most well-known examples of a more bird-like dinosaur was “Archaeopteryx”, an organism that lived around 150 million years ago and had feathers and wings like a bird but still had teeth and a bony tail like a dinosaur3,7. Asteriornis Maastrichtensis, or now referred to as the “wonderchicken”, lived around 66.8 – 66.7 million years ago. This is very close (in geologic time) to a really significant event in geologic history. You may recall from our post on fossilized pollen that the dinosaurs went extinct around 65 million years ago. The discovery of this fossil has given paleontologists a better idea of when more modern birds evolved from dinosaurs. And, once birds evolved, bam! They diversified like crazy2 to bring us the 9,000 – 10,000 bird species we have today8.

Can a dinosaur do the chicken dance?

We’ve talked a bit about how challenging it is to confidently know what a specific dinosaur exactly looked like from fossils. For example, it’s hard to know for sure what the texture or color of a dinosaur’s skin was from fossils of its bones (though impressions of skin texture can be preserved9). Something that we can begin to hypothesize is how a dinosaur moved. One way we can do that is through dinosaur footprints. Footprints are trace fossils, meaning they provide us with clues as to how the animal moved and where it lived but are not actually a preserved part of the body. Dinosaur tracks (or paths of tracks called “trackways”) tell us about how large the stride of the animal was. Parallel tracks that likely belong to multiple dinosaurs tell us that movement may have occurred in a herd10.

Scientists can even use body dimensions to hypothesize how a dinosaur moved using computer modeling. For example, a recent scientific paper published a few months ago used the large size of a T. Rex’s tail to model how fast the dinosaur would have been able to walk. Using computer models, this study concluded that the T. Rex walked at a rate of about 2.86 miles per hour11,12. As far as top speeds, other studies hypothesize that the T. Rex may have been able to run at around 12 miles per hour13. Check out the video of a T. Rex walking at its “natural frequency”, meaning where it balances its large tail11.

Video by: Rick Stikkelorum, Arthur Ulmann, and Pasha van Bijlert based on work from11

Now what about chickens? These graceful (just kidding) birds have a top speed of around 9 miles per hour14. Check out the video below, slowed down to enjoy the excitement of fresh prey: a snack of dried mealworms.

Video by: Kristen Rahilly. Chickens: Bonnie, Nancy, and Miss Trish

References:

1McKeever, Amy. Why Tyrannosaurus rex was one of the fiercest predators of all time. National Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/facts/tyrannosaurus-rex, accessed 14 July, 2021.

2Brusatte, Stephen L et al. “Gradual assembly of avian body plan culminated in rapid rates of evolution across the dinosaur-bird transition.” Current biology : CB vol. 24,20 (2014): 2386-92. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2014.08.034

3Singer, Emily. How Dinosaurs Shrank and Became Birds. Quanta Magazine, 2 June, 2015. https://www.quantamagazine.org/how-birds-evolved-from-dinosaurs-20150602/, accessed 13 July, 2021.

4Hendry, Lisa. How are dinosaur fossils formed? The Natural History Museum, London, https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/how-are-fossils-formed.html, accessed 14 July, 2021.

5Field, Daniel J., et al. “Late Cretaceous neornithine from Europe illuminates the origins of crown birds.” Nature 579.7799 (2020): 397-401.

6Briggs, Helen. Fossil ‘wonderchicken’ could be earliest known fowl. BBC News, 18 March, 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-51925335, accessed 13 July, 2021.

7Australian Museum. Bird-like dinosaurs. Australian Museum, 26 November, 2020, https://australian.museum/learn/dinosaurs/bird-like-dinosaurs/, accessed 14 July, 2021.

8New Study Doubles the Estimate of Bird Species in the World. American Museum of Natural History, https://www.amnh.org/about/press-center/new-study-doubles-the-estimate-of-bird-species-in-the-world, accessed 14 July, 2021.

9Skin. American Museum of Natural History, https://www.amnh.org/exhibitions/sauropods-worlds-largest-dinosaurs/outside-mamenchisaurus/skin, accessed 14 July, 2021.

10Osterloff, Emily. Dinosaur footprints: how do they form and what can they tell us? Natural History Museum, London, 19 December, 2019, https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/dinosaur-footprints.html, accessed 13 July, 2021.

11Van Bijlert, Pasha A., AJ ‘Knoek van Soest, and Anne S. Schulp. “Natural Frequency Method: estimating the preferred walking speed of Tyrannosaurus rex based on tail natural frequency.” Royal Society open science 8.4 (2021): 201441.

12Gamillo, Elizabeth. New Study Finds T. Rex Walked at a Slow Pace of Three Miles Per Hour. Smithsonian Magazine, 23 April, 2021, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/new-study-finds-that-t-rex-walked-at-slow-pace-of-3-miles-per-hour-180977572/, accessed 13 July, 2021.

13Montanari, Shaena. Actually, you could have outrun a T. Rex. National Geographic, 18 July, 2017, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/tyrannosaur-trex-running-speed, accessed 14 July, 2021.

14Buckley, Chad E. “Speed is Relative (Human and Animal Running Speeds): Are You a Cheetah, a Chicken, or a Snail?” (2013). Faculty and Staff Publications – Milner Library, 46.